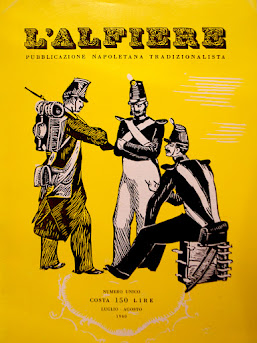

“Ferdinando II” di Silvio Vitale was translated with permission from L’Alfiere: Pubblicazione Napoletana Tradizionalista, Numero Unico, Luglio-Agosto 1960, pp. 3-5. Illustrations reprinted from the magazine.

Ferdinando II

by Silvio Vitale

The colorful phraseology, juicy anecdotes, and frank popular tales about Ferdinando II of Bourbon, as handed down by Salvatore Di Giacomo and Nicola Nisco, are well known.

Liberal historiography, with a unanimity as unjust as it was sinister, then launched a perverse series of accusations and insults on this intransigent and sarcastic King.

Ferdinando II went down in history (the one celebrated today by the exalters of the conspiracies and betrayals of a century ago) as a vulgar and tyrannical man, his government as "the denial of God".

On the other hand, the restless spirits in eternal agitation, the instigators of a thousand useless disorders, the slanderous and perjured sectarians, sharp of tongue as of dagger, the free thinkers anticipating the pitfalls and the technique of today's democratic factions, are worthy of the name in all capital letters in texts on civic education, deserving of the laurel in the oleographs that the magazines prepare us, and "fathers of the country,” from which only the Kingdom of Italy, then the Republic, can draw legitimacy.

Well, to believe that Ferdinando II was the monster that Settembrini and Gladstone portray is as senseless as admitting that Garibaldi was the “brother of Santa Rosalia” and Mazzini an “apostle.”

Ferdinando II had a pessimistic view of men in general, but he knew how to appreciate righteousness and valor as soon as it was revealed to him.

He despised and ridiculed the “pennaruli,” [pseudo intellectual scribblers] believing that the only literature useful to the State was that of magistrates and ecclesiastics.

He was inexorable against flattery, hypocrisy and dishonesty; and he didn't hesitate to brand these turpitudes with sudden sarcastic remarks, which hit the mark and did not allow for replies.

He is reproached for having tyrannized ministers and people, but it is also true that, if he had not done this, a society poisoned by the sectarian spirit, such as that which besieged the Court with flattery and threats, would have done him under.

It was certainly not necessary to glean Machiavelli for an attentive monarch to aim not to be taken by surprise and to dominate men and things in order not to be overpowered by them.

When in 1848 the Neapolitan sectarians, who wanted to "carry out" the Constitution in order to overthrow the Throne, armed with patriotic scowls, unfortunate furniture and a few muskets, set about building barricades, he sent to tell them not to "do foolish things and go home." The contempt with which he showered his adversaries, which did not allow him to take them seriously into consideration, was also an art of government, a good-natured, but firm way of mastering them.

In relations with his subjects he was absolute King and it is ridiculous to charge him with wanting to be such, that is, that he held his rank and in his place in perfect coherence.

In relation to the Church he was humble and fervent believer, but at the same time he did not renounce to call himself King of divine right, deriving power immediately from Heaven, without intermediaries and mortgages on temporal affairs within his jurisdiction.

Extremely jealous of his own independence, he was equally respectful of others'. Several times the liberals had offered him to be the promoter of the Italian unitary movement, arousing his ambition for territorial enrichment. He wanted to remain firm only to his legitimate rights and did not allow himself to be drawn to their side.

He had no sympathy for the interests and interventions of others in the peninsula, be they British, French or Austrian. In fact, the foreign pressure in the Kingdom under Championnet, Nelson, Joseph-Napoléon, Murat and the Austrian contingents of 1821 had been very strong, caused by the continuous internal disturbances carried out by the sectarians. And the history of the Bourbons of Naples appears as a continuous effort for independence, a jealous tendency to fully exercise sovereignty.

Ferdinand II was a good fighter. When the sword of Agesilao Milano (one of the many exalted implementers of Mazzini's dagger doctrine) suddenly hit him, on the Campo di Marte, he remained upright in his place, so much so that only the closest ones noticed the fact and caught the criminal. He knew that he could, at any moment, pay in person—it was so much part of his duties as King.

The seriousness of the event did not move the gazettes. But how many whined over the execution of the Bandiera brothers, deserters from the Austrian navy, or for the suicide of Carlo Pisacane? As unfortunate as they are reckless, how many complaints about the chains on the wrists of Luigi Settembrini, Silvio Spaventa and Carlo Poerio? Historians say that they were forced to live alongside ordinary prisoners, ferocious criminals, and they are scandalized by them. But it is true that in prison the "pennaruli" did not hesitate to get together with the criminals and did such a proselytizing work that the latter then found themselves, in 1860, alongside Liborio Romano in undermining the last defenses of the Bourbon Kingdom against the sectarians and Garibaldi's action.

The names of Bandiera, Pisacane, Settembrini have been the highlight of liberal historiography. But how much injustice in forgetting the other barricade? After 1860 how many heroes did not fall under the lead of the Piedmontese repression, shot on the spot, without trial and covered by the conspiracy of silence?

The ire of the liberals was also thrown against the Ferdinando II of 1848. They say, “The King had the people shot.” But they forget that the "pennaruli" had created such a mess as to destroy social peace and had incited hordes of naive people against the King.

Ferdinando II had promulgated the Constitution as a pledge of peace with the tireless agitators. And at the same time he had brought them the sword with the blade side inviting them to prove their good faith. It was a skillful move in a very difficult moment for the fate of Europe, a moment that would even have marked the downfall of a Metternich.

The Neapolitan deputies aimed to take the Constitution much further. They claimed to "carry out" the charter, as has been said before, by refusing to swear or recognize the authority to the King's ministers and supporting the revolt in Calabria and Sicily which had declared the Bourbon King deposed. While the army, sent in the North alongside Carlo Alberto without even the guarantee of a military alliance pact, was absent from Naples, he seemed to support the Italian cause in Lombardy. In reality he left the Kingdom of Naples at the mercy of the rioters.

Who then broke the covenants? Who was the first to nullify the Constitution, which obviously had to be based on the good faith of the implementers in order to be implemented? Let it not be said that because Ferdinando II had sworn to the Constitution, he alone, and not convinced, should have observed it, while all the others in fact denied it, and this they did to take away the solidity and life of the Throne itself.

The accusation of perjury is then the most miserable of all that the liberals have launched against the King of Naples.

The least he could do in those circumstances was to suspend the Constitution, placing the sum of power in his hands and, with war declared, accept the challenge. After all, the Constitution was ungrateful to most, who were tired of sectarian intrigues, and they too took to the streets to ask for its abolition.

So Ferdinando II in 1848 was the first sovereign in Europe to start the reaction against the conspiracy that had shocked the whole continent. He tamed it without outside help, proudly alone.

The army put down the insurrection of May 15 with valor, reconquered Sicily and pacified Calabria, while it had already fought with strenuous courage in the fields of Lombardy.

It was an excellent troop which was flanked by the strongest navy in Europe, superior to those of the other Italian states. The Neapolitan navy was destined to excite the greed of Cavour, who later adopted the ordinances, maneuvers, flag signals, which the Sardinian fleet lacked.

Just as Ferdinando II had lived, he died serene and secure. In 1859 the tragedy of the Kingdom was gathering. When he learned of Austria's ultimatum to Piedmont he expressed the same negative judgment as Metternich. Franz Joseph's act would have been fatal. When he learned that Leopoldo of Tuscany had abandoned the throne out of cowardice, he said that, having gone away, "he was not worthy to stay there.”

He witnessed the decomposition of the body and the slow advance of death having more faith in God than in doctors. And even for this he was reproached!

Before leaving he called the Crown Prince to him and while he had breath he told him "not to compromise with the revolution.”

After receiving the holy oil, he embraced and blessed all his family members and said: “At this moment the Lord is giving me the grace to be calm and not to suffer any displeasure of detaching myself from the people and things I love the most: I leave the Kingdom, the greatness, honors, riches, and I feel no displeasure. I have tried as much as I could to fulfill the duties of a Christian and a sovereign. I thank the Lord for enlightening me."