|

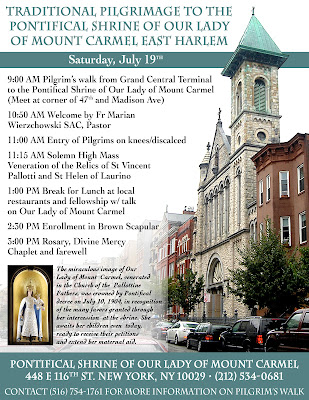

| Madonna Degli Infermi, ora pro nobis |

July 13, 2025

Feast of the Madonna Degli Infermi

Feast of St. Mildred of Thanet

|

| St. Mildred of Thanet, ora pro nobis |

In celebration, we’re posting a prayer to St. Mildred of Thanet written by M. Lee Boseman. The accompanying photo comes courtesy of Father Eugene Carrella. The holy card is part of Father Carrella’s impressive collection of religious artifacts. Evviva St. Mildred of Thanet!

Prayer to St. Mildred of Thanet

Good Saint Mildred, sweet flower of perfection and charity, while on earth, you rejected the riches you had been born of and gave your life to Christ. You are well known for your sincere love and compassion for the poor; please pray for us that we may be pleasing to God by accepting His Holy Will. And in accepting His Holy Will may we be less concerned with our own sufferings and more eager to help others in need as you did. Remember also my special intention(s) I now faithfully entrust to you. (Name your special intentions) Pray for us Saint Mildred that we may be made true servants of Christ and share in the eternal joys of heaven with God Our Father. Amen

Feast of Santa Trofimena di Minori

|

Santa Trofimena di Minori, ora pro nobis |

|

| (L) Santa Trofimena, Williamsburg, Brooklyn. (R) Santa Trofimena, New Haven, Connecticut |

July 12, 2025

Simple Pleasures: Curva Sud Matera Sticker

Feast of Santa Veronica

|

| Santa Veronica, ora pro nobis |

July 11, 2025

Ponderable Quote from ‘La Monarchia Tradizionale’ by Francisco Elías de Tejada

Translated from the Italian*

The Universal Christian Enterprise

The tradition of Naples is unanimously lived and expressed by the greatest writers of the kingdom, who are enemies of Luther, of Machiavelli, of Bodin, of Hobbes—in a word, of all the fathers of Europe. Against the first of these, Luther, it was a son of Gaeta, Tommaso de Vio, who opened the Catholic polemic, even though not the slightest tentacle of Lutheran heresy ever emerged in Naples, since the Waldensians had no other relation to Naples than that of a momentary stay: Juan de Valdés was from Cuenca, Bernardino Tommasini of Oca was Sienese, Pietro Carnesecchi and Pietro Martire Vermigli were Florentine, Marc’Antonio Flaminio was Venetian, Giulia Gonzaga was Lombard, and Isabel Briceno was Iberian. Nor did Machiavellianism ever gain a foothold in Naples, because the very Neapolitan school of Tacitean realism was by nature anti-Machiavellian. Among its ranks are names of the stature of Girolamo Franchetta, Fabio Frezza, Deodato Solerà, Gio. Donato Turboli, Muzio Floriati, Giambattista Vico, and many others—not to mention that one of the most formidable anti-Machiavellian polemicists known to us was born in Rocca d’Evandro, in the Terra di Lavoro: Ottavio Sammarco. Moreover, there were thinkers who did not even admit Tacitism (due to their extremely realist stance), such as Alberto Pecorelli or Giulio Cesare Capaccio, or the courageous polemicist Torquato Accetto, engaged in combatting Machiavelli from the trenches of Stoic philosophy. The absolutist mentality typical of Europe and unknown in the Spains, theorized by Jean Bodin in Les six livres de la République, was incompatible with the mentality of traditional Naples, because the latter upheld the subjection of the prince to the laws of the Kingdom, in the unanimous doctrine of Neapolitan jurisprudence, synthesized by the free subjects of Philip II in the much-forgotten yet sublime text of Giovanni Antonio Lanario, according to whom: “Potestas absoluta non potest dari in Republica politica, et bene ordinata” (“Absolute power cannot be granted in a political and well-ordered Republic”). This doctrine was developed by Alessandro Turamino in his vision of custom as an expression of the popular will; by Andrea Molfesio in his framework of legal limitations; by Domenico Tassone in his chart of institutional limitations; by Francesco Pavone in his conception of popular customs as superior to the laws of the prince; and by many others whom it is not necessary to list in order to clarify the concept of limited power characteristic of the Spains—which placed authentic Naples in a position of opposition to the Bodinian absolutism characteristic of Europe. The systematic body of Neapolitan parliamentary law developed by the Bishop of Capri, Raffaele Rastelli, in the time of Philip IV, would alone suffice to make clear the contrast between Neapolitan political law—free, with a Spanish imprint—and European political law.

* La monarchia tradizionale, Francisco Elías de Tejada, Capitolo Settimo, La Tradizione di Napoli, 4 L’impresa universale cristiana, 1963, P.153-154, Controcorrente Edizioni, 2001, P.142-144

Feast of St. Oliver Plunket

|

| St. Oliver Plunket, ora pro nobis |

In celebration, we’re posting a prayer to St. Oliver Plunket. The photo comes courtesy of Father Eugene Carrella. The statue and "ex ossibus" relic of St. Oliver Plunket is part of Father Carrella’s impressive collection of religious statuary and relics. Evviva St. Oliver Plunket!

Prayer to St. Oliver Plunket

Glorious martyr, Saint Oliver Plunkett, who willingly gave your life for the faith, help us also to be strong in our faith. By your intercession and example may all hatred and bitterness be banished from the hearts of men and women. May the peace of Christ reign in our hearts as it did in your heart even at the moment of your death. Amen.

July 10, 2025

Random Thoughts as the Buck Moon Approaches

As the hart panteth after the fountains of water, so my soul panteth after thee, O God. ~ Psalm 41:2 DRB

This year, July’s full “Buck Moon” falls on the 10th. The name comes from the time of year when male deer start to regrow their antlers. Popularized by the Farmer’s Almanac in the 1800s, the term was reportedly adopted by the pioneers from the Native Americans. It is also known as the “Thunder Moon,” due to July’s frequent storms; the “Hay Moon” for the hay harvest; and the “Mead Moon,” marking the season when honey was traditionally gathered to brew mead, an ancient and tasty fermented honey beverage.

Unable to find real mead in time, I thought we would instead mark the occasion with a few shots of Bärenjäger and Jägermeister, along with a little moon bathing, weather permitting. Traditionally, in Naples, moonlight bathing is believed to cure both physical and spiritual ailments.

Long fascinated by the moon and other celestial bodies, La Luna is a medieval symbol of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Just as the moon reflects the light of the sun, Mary reflects the divine light of her Son, Our Lord Jesus Christ.

The stag, on the other hand, embodies Christ and is a messenger of divine truth. Just as the stag tramples the serpent underfoot, so does Our Lord crush Satan. The shedding of antlers serves as an allegory for renewal and resurrection.

The stag bathing in springs symbolizes baptism and the Church’s role in guiding the faithful to the sacred waters of eternal life. The motif of the hunted stag pierced by arrows, as seen in the hagiographies of Sant’Eustachio Martire and Sant’Uberto di Liegi, represents both the Passion of Christ and, more broadly, the martyrdom of the saints.

With more than a few hours to kill before the astronomical event, I plan to browse my poetry books for a few poems to read to my guests after dinner. I already know I will recite Salvator Di Giacomo’s Luna Nova (New Moon) and Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Cervo (The Deer). Hopefully, I will find a couple more suitable for the evening.

An excerpt from D’Annunzio’s Il Cervo:

Udremo a notte le sue lunghe

muggia, udremo la voce sua di toro;

sorgerà il grido della sua lussuria

udremo nei silenzi della luna.

At night we will hear his long

bellows, we will hear his voice like a bull’s;

the cry of his lust will rise

we will hear it in the silences of the moon.

And from Di Giacomo’s Luna Nova:

Luna d’argiento, lass’ ‘o sunnà,

vaselo ‘nfronte, nun ‘o sceta…

Silver moon, let him dream,

kiss his brow, do not wake him…

~ By Giovanni di Napoli, July 9th, the Feast of Santa Veronica Giuliani

Feast of Santa Rufina and Santa Seconda

Orate pro nobis, Sante Rufina e Seconda

Præsta, quæsumus, omnípotens Deus: ut, qui gloriósos Mártyres fortes in sua confessióne cognóvimus, pios apud te in nostra intercessióne sentiámus. Per Dóminum.

July 10th is the feast of Saints Rufina and Secunda, Virgins and Martyrs of Rome. Daughters of a Roman Senator, the pious sisters were betrothed to Christian men who renounced their faith for fear of persecution. Refusing to get married to the apostates, the girls consecrated their virginity to Our Lord Jesus Christ. Unwilling to break their vow, they were apprehended and tortured by the prefect Giunio Donato. Beaten and scourged, their captors were unable to get the girls to renounce their faith. Condemned to death, the sisters had weights fastened around their necks and tossed into the Tiber River, however instead of sinking an angel kept them above water. Finally, led ten miles on the Via Cornelia, Rufina was beheaded and Seconda was clubbed to death.

In celebration, we’re posting a prayer in Latin and English to Saints Rufina and Secunda as well as the Holy Seven Brothers, Martyrs, who are also commemorated on this day. The painting of The Martyrdom of Saints Secunda and Rufina was a collaboration by Il Morazzone, Giulio Cesare Procaccini and Il Cerano. Evviva Santa Rufina e Santa Seconda!

Prayer to Saints Rufina and Secunda, and the Holy Seven Brothers

Grant, we beseech Thee, O almighty God, that, we, who have known the courage of the glorious martyrs in their confessing Thee, may experience their kindness in interceding for us with Thee. Through our Lord.

July 9, 2025

"The Family: Burden or Bulwark?" On the Right’s Abdication of Cultural Power

Gianandrea de Antonellis’ Il seminarista rosso (The Red Seminarian) is a bold and piercing reflection on one of the most overlooked strategic failures of the Right: its abdication of the cultural front in the battle for the soul of modern society—particularly as it pertains to the Church, the seminaries, and the family. This work isn’t simply a lament for lost ground; it’s a sharp and historically grounded diagnosis of how the Left—with Gramsci as its prophet—waged and won a cultural war while the Right remained disorganized and politically impotent.

One of the most illuminating and provocative sections of the essay is the author’s meditation on La famiglia, peso o baluardo? (The Family: Burden or Bulwark?) and the legacy of Julius Evola, offered as a kind of anti-Gramsci—the closest figure the Right has had to a revolutionary thinker with a coherent meta-political project. Evola, ever the radical aristocrat, saw clearly the need for a new type of man—free from bourgeois sentimentality, unattached to domestic comforts, and trained for the spiritual combat of tradition in an age of decline. De Antonellis explores the Sicilian Baron’s uncompromising stance on celibacy and sexual freedom for militant traditionalists, which, while sure to scandalize mainstream conservatives, is consistent with Evola’s ruthless logic: one cannot wage metaphysical war while clinging to hearth and family life.

This reading of Evola—as someone who, like Gramsci, understood the gravity of the cultural battlefield—is perhaps the most compelling and sobering contribution of the essay. Evola’s failure, as De Antonellis points out, was not intellectual but practical: the Right never produced an “army” of Evolian men who could live sine impedimenta—unbound by work, marriage, or social conformity. The “chimera” of revolutionary struggle almost always gave way to the “siren” of love, comfort, and family—a tragic inversion of priorities for a movement that claims to uphold heroic virtue and transcendent order.

De Antonellis is not dismissive of the family—far from it. He presents it as a natural and deeply rooted good, a bastion of civilizational continuity. But he does not allow this to become an excuse for passivity or withdrawal. Rather, the essay challenges the Right to reconsider the cost of its values when confronted with revolutionary zeal. The Left was willing to send its sons into seminaries, into newspapers, into cultural warfare. The Right, by contrast, hesitated to sacrifice—not because it lacked conviction, but because it lacked coordination, imagination, and above all, a counter-cultural elite capable of forming a long-term resistance.

La famiglia, peso o baluardo? is not just a lamentation of missed opportunities—it is a call for the Right to reorient itself around strategy and sacrifice. It reminds us that culture is not an idle pastime, but the foundation of power. And in highlighting Evola’s challenge—the demand for a militant, metaphysical manhood (società di uomini, or Männerbund)—De Antonellis invites his readers to reconsider what kind of men must rise if the tide is ever to turn.

This is an essential read for any counter-revolutionary thinker who is done making excuses and ready to confront the hard truths of civilizational decline.

~ By Giovanni di Napoli, July 8th, Feast of San Procopio di Cesarea

Feast of Santa Veronica Giuliani

|

| Santa Veronica Giuliani, ora pro nobis |

“It is not time to rest but to suffer.” ~ Diary of Santa Veronica GiulianiJuly 9th is the Feast of Santa Veronica Giuliani (1660-1727), Capuchin Poor Clare and Mystic. Owing to a quaint childhood anecdote, she is the patron saint of fencers (schermitori). According to tradition, she was upset with an older cousin who was neglecting his prayers in order to practice fencing. Challenging him to a duel, she wounded him in the hand just enough to make him rest and contemplate his poor decision. With a deep-seated devotion to the Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ, she entered the Capuchin convent at Città di Castello in Umbria at the age of seventeen. Subject to numerous celestial and infernal visions, she received amid untold sufferings the gift of the stigmata, the Crown of Thorns, and Mystical Espousal to Christ. In celebration, I’m posting a prayer to St. Veronica Giuliani. The accompanying photo of Santa Veronica Giuliani was taken at the Chiesa Parrocchiale della SS. Immacolata in Salerno, Campania. Evviva Santa Veroniva Giuliani!

Prayer to St. Veronica Giuliani

O Lord Jesus Christ, who did glorify St. Veronica by the marks of Thy suffering grant us the grace to crucify our flesh and thus become worthy of attaining to the joys of eternity. Who lives and reigns forever and ever. Amen.

Feast of San Pancrazio di Taormina

|

| San Pancrazio di Taormina, ora pro nobis |

July 9th is the Feast of San Pancrazio di Taormina, Bishop, Missionary and Martyr. He is the patron saint of Taormina (ME) and Canicatti (AG) in Sicily. Born in Antioch, Cilicia, he visited Jerusalem as a young boy with his father to see Our Lord Jesus Christ in person. Returning to Antioch, the youth was baptized and instructed in the Faith by St. Peter. In due course St. Peter sent San Pancrazio to Sicily and he became the first bishop of Taormina. He was stoned to death by pagans for refusing to kiss a graven image.

In celebration, I’m posting the prayers to St. Pancratius, Hieromartyr from Byzantine Catholic Prayer for the Home. They are meant for private use.

Pictured is a detail of the Martyrdom of San Pancrazio di Taormina from the 2015 feast program. Evviva San Pancrazio Vescovo!

Troparia

Troparion Tone 8 Like an arrow on fire, you were aimed at Tauromeno to kill the godless and to bring light to the faithful of that place. You strengthened them in the faith by your preaching, and you finished your work by spilling your blood. O martyred priest, Pancratius, pray for your flock and for all who cherish your memory.

Kontakion Tone 4 You appeared to the people of Tauromeno as a star, and you became a martyr-priest for Christ, Pancratius. As you stand before Him, pray for us who love you.

Stichera from for a Hieromartyr.

Sessional Hymns from the weekday.

July 8, 2025

Feast of San Procopio di Cesarea di Palestina

|

| San Procopio di Scitopoli, ora pro nobis |

July 8 is the Feast of San Procopio di Cesarea di Palestina (also San Procopio di Scitopoli), Ascetic, Exorcist and Martyr. A native a Aelia Capitolina, Jerusalem, Procopius was the first Christian to be martyred in Palestine under Emperor Diocletian’s decree of persecution in 303. He is the patron saint of San Procopio in Reggia Calabria.

In celebration, I’m posting the prayers to St. Procopius the Great from Byzantine Catholic Prayer for the Home. They are meant for private use.

The accompanying image depicts the great protomartyr as a holy warrior. Evviva San Procopio di Scitopoli!

Troparia

Troparion Tone 8 Receiving heaven's invitation, O saint, you turned from ancestral infamy and traditional homage, begging zealous like Paul for Christ. You endured many tortures and wounds, and you have been repaid with a crown of glory; so pray to Christ to save us, O great martyr Procopius.

Kontakion Tone 2 Inflamed with a heavenly zeal for Christ, and protected by the might of the Cross, you leveled the rages and the gall of the fire. You raised up the Church, O Procopius, by the strength of your faith. You enlighten us!

Stichera from For a Martyr.

Sessional Hymns from the weekday.

Feast of Santa Elisabetta of Portugal

|

| Santa Elisabetta, ora pro nobis |

Prayer to St. Elizabeth of Portugal

Father of peace and love, you gave Saint Elizabeth the gift of reconciling enemies. By the help of her prayers give us the courage to work for peace among men, that we may be called the sons of God. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Download Il Portastendardo di Civitella del Tronto from Telegram

July 7, 2025

Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel

|

| Our Lady of Mt. Carmel at Most Precious Blood Church, Little Italy, NYC |

Pray Novena to Our Lady of Mount Carmel for nine consecutive days, July 7th to July 15th, in preparation for the Feast on July 16th. Ave Maria!

Flos Carmeli (Flower of Carmel)

O most beautiful flower of Mount Carmel, splendor of heaven, Blessed Mother of the Son of God and Mother of mine, support me by your never failing love and help and protect me. Show me that you are my Mother. May I, unworthy as I am, come one day to exchange your scapular that I had the privilege to wear for the wedding garment of heaven, and dwell with you and all the saints of Carmel in the kingdom of your Son. (Here make your petition: Let us also pray for those preparing to make their vows.) Sweet Mother, I place this cause in your loving hands. O Mary, my Mother, I consecrate myself to you forever. I offer you my body with all its miseries, my soul with all its imperfections, and my heart with all its affections and desires. I offer you all my prayers, works, joys and sufferings, my struggles and especially my death with all that it will entail. I unite all of these, Mother, with your own joys and sufferings. Amen.

Queen and Beauty of Carmel, pray for us.

Photo of the Week: Ivory Oliphant Fragment

July 6, 2025

Introducing "Il seminarista rosso: L'infiltrazione marxista nella Chiesa" by Gianandrea de Antonellis

Il seminarista rosso, or The Red Seminarian, is a powerful and meticulously researched exposé of the ideological infiltration that has shaped the modern Catholic Church from within. Tracing the furtive paths of Marxist and modernist influences, Gianandrea de Antonellis presents a bold and provocative account of the post-conciliar Church, while maintaining focus on the profound spiritual and cultural ramifications at hand. Supported by extensive footnotes and documentation, the author draws upon a wide array of ecclesiastical, political, and philosophical sources.

Though lengthy, the following quotations are essential for understanding the full scope of the author’s argument.

“In the case of the 'revolution in the Church'—that is, the Second Vatican Council—it did not arise out of nowhere, but was carefully prepared in the decades preceding it. Its promoters were, on one hand, the modernists, who had been exposed but not eradicated by Pascendi; [1] on the other hand, the new anti-Christian forces of Marxist origin. Both modernists and communists were united in the project of destroying the traditional Church from within rather than from without, as had been attempted previously (to cite only the main cases of the last millennium) by the Albigensians, Protestants, advocates of national churches (gallicani, giuseppinisti, etc.), [2] Enlightenment thinkers, Jacobins, jurisdictionalists, liberals (Kulturkampf, desamortización, guarentigie), [3] and, in the last century, Spanish anarcho-socialists and German National Socialists.

“A precedent for this ‘struggle from within’ can be found in the ‘underground’ movement of Jansenism (17th century), which in Italy found its most significant expression in the Synod of Pistoia (1786). [4] The movement, which takes its name from the Bishop of Ypres, Cornelius Otto Jansen (Latinized as Jansen or Giansenio, 1585–1638), sought to implement a semi-Calvinist reform while never formally leaving the bosom of the Church, attempting instead to infect it from within. Because of its elitist character, however, it remained relatively isolated: its ‘coming to light’ at the Synod of Pistoia even provoked a popular uprising, as it sought to abolish certain devotions deeply cherished by the faithful.”

With a seamless blend of theological critique and historical analysis, de Antonellis reveals recurring patterns of subversion and doctrinal compromise.

“Iconoclasm and the abolition of side altars, the use of the vernacular language in the liturgy, and episcopalism or conciliarism (that is, considering the bishops’ conference as the head of the national Church while leaving to the pope the simple role of unus inter pares), [5] proposed by the Synod of Pistoia and immediately condemned, were triumphantly accepted with the Council and its ‘spirit.’

“The disruptive force of the neo-modernist mentality nonetheless comes from elements of extra-ecclesial formation: namely the Marxist infiltrators who, in the wake of Stalin’s consolidation of power in the USSR and the subjugation of the Orthodox Church, were tasked with weakening the Catholic Church, undertaking a long-term effort that offered promising prospects and—eighty years later—an almost unexpected success.

“In the 1930s, the secret services of the Soviet Union employed every kind of stratagem, even the most Machiavellian, in order to ‘plant the seed of ideological counteroffensive in the very heart of Western democracies and even within the fascist states themselves, beginning with Mussolini’s Italy, where they could serve in the dual role of fifth columns within the Catholic Church and agents of political espionage with an anti-capitalist and anti-bourgeois orientation.’ [6]

“This infiltration naturally continued after the Second World War: during the years of the Cold War, a significant number of Soviet secret service members—Italians, French, Germans, and so on, all young people of proven Marxist-Leninist conviction—skillfully infiltrated not only the vital organs of civil society in Western countries (newspapers, publishing houses, courts, labor unions), but also the ranks of the Catholic Church, starting at the level of priestly formation—that is, in seminaries and novitiates—with the specific mandate to subtly implant communist ideas into the mentality and practice of the clergy.”

He gives particular attention to the role of the Jesuit order, liberation theology, and the cultural upheavals that followed the Second Vatican Council.

“A privileged instrument in this infiltration project has been the Society of Jesus. Whereas in the past the Jesuits were the arch-enemies of Freemasonry (which even succeeded in having them suppressed by the Holy See), they have now become its preferred tool, ‘with the precise aim of achieving a ‘normalization’ of relations with Freemasonry.’ With the ascent of a Jesuit to the papal throne, it is fair to ask: ‘What use will be made, by the religious order by far the most powerful, the richest, the most learned, the most adaptable, the most adventurous, the most cunning in political and diplomatic experience, the best connected with the secular world, with other religions, and with Freemasonry itself, as well as with international high finance, of its immense power?’ [7]

“In truth, the Jesuit order has long been only outwardly the same as it was in past centuries: already by the mid-twentieth century, certain members of the order—such as Teilhard de Chardin—stirred polemics and controversy with their bold theological positions; others, like Karl Rahner, openly advocated for a radical reform of the Church, and vigorously promoted this agenda, even within the halls of the Second Vatican Council.

“That very Council has been interpreted, by more than one observer, as an attempt to implement the comprehensive reform envisioned by Rahner and others—a trend that was then developed and deepened under the influence of liberation theology, which also arose—not coincidentally—in Latin American Jesuit circles.

“The Council was followed by the so-called 'spirit of the Council,' that is, the broad interpretation of the deliberately ambiguous conciliar documents. This is why, from a Novus Ordo (the modern Mass) that was originally intended to stand alongside the traditional liturgy, there emerged a practical suppression of the latter.”

I found de Antonellis’ take on the failure of the counter-revolution to be especially compelling. Once more, I quote at length—though not without cause.

“Why did the infiltration of seminaries occur through members or sympathizers of the Communist Party, and not through elements of the Right? Why was there no right-wing response to the hegemonic Marxist strategy? Why—to broaden the discussion—were leftist publishing houses not met with a corresponding network of right-wing publishers, essayists, novelists, or journalists? In reality, attempts were made, but what was lacking—even more than substantial funding like the so-called ‘Moscow gold’—was coordination among the various forces at play.

“In a single phrase, the reason for the overwhelming cultural victory of the Left can be summed up by saying that what the Right lacked was a figure like Gramsci: a thinker who understood the fundamental role of culture, and a Party that recognized this role as primary (regardless of Gramsci’s personal life or his relationship with the Party’s leader, Togliatti).

“But this does not mean that the Right has lacked significant thinkers. On the contrary: I won’t list them—it would be too long—because, ultimately, from Homer to the mid-twentieth century, the greatest writers, philosophers, and poets have essentially been on the Right, meaning religious, monarchist, meritocratic, aristocratic, and anti-democratic (just consider how Homer, in the Iliad, encapsulates the democratic spirit in the figure of Thersites…). [8] What has been entirely lacking, however, is a great man of culture who was recognized and valued as such: ‘When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver’—a now-famous phrase from a virtually unknown author, often casually attributed to various right-wing political figures, from Göring to Goebbels, Codreanu, or Primo de Rivera.

“Culture has always been regarded as the pastime of the idle (in the etymological sense, from otium): only those with a stable economic position can afford it. It was therefore unthinkable to make political journalism or literature a profession. The consequence is that—with a few numerically insignificant exceptions—those who wished to combine a cultural vocation with the need to earn a living had to either join a leftist newspaper, magazine, or publishing house, or else find a day job and, in their free time, dedicate themselves to writing not as professionals, but as amateurs. The result has been the dispersion of right-wing culture into a thousand insignificant rivulets.

“Just as there has been no ability to channel the cultural potential of the Right, so too has there been no ability to direct its political potential. It would therefore be inconceivable to ask a group of young people to choose the ‘cloistered path’ for a long-term project to stop the revolution in the Church from within. Certainly, there will be young people with vocations (who, today, will find modernist seminaries with modernist teachers and, once ordained, will celebrate modernist rites under the watchful eye of modernist bishops), but they will be a tiny minority. Why not then consider the entrance of traditionalists into seminaries to counter the revolution in the Church?

“In addition to the lack of an organization encouraging young militants to enter the seminary, this idea of sacrifice (which should not, in fact, be seen as such) clashes with the deep attachment of the Right-wing man to the value of the family, the fundamental nucleus of society: generally, he finds it difficult to renounce family life, even for a prestigious career. He will instead try to reconcile public and private life, work and family—perhaps sacrificing the latter to the former, but never entirely abandoning it, except in rare cases.”

Far from being a mere denunciation, Il seminarista rosso is an unflinching and intellectually rigorous call to vigilance. It compels readers to confront uncomfortable truths about the Church’s modern decline and to recover a restored obedience to tradition, spiritual authority, and metaphysical truth.

A vital contribution to the contemporary Catholic discourse, Gianandrea de Antonellis’ essay deserves a wide readership among all who care about the fate of Catholic tradition in the twenty-first century.

A PDF copy of Il seminarista rosso: L'infiltrazione marxista nella Chiesa can be downloaded at www.altaterradilavoro.com

~ By Giovanni di Napoli, Feast of the Madonna Immacolata

Translation and footnotes are my own unless otherwise indicated.

Notes

[1] Pascendi refers to Pascendi Dominici Gregis, a papal encyclical issued by Pope Pius X on September 8, 1907. It is one of the most important documents of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of Modernism.

[2] Gallicani (Gallicanism) was a political-religious movement that emerged primarily in France, especially during the 17th and 18th centuries, with earlier roots in the Middle Ages. It sought to limit the authority of the pope, particularly in temporal and national matters, and to increase the power of the national church and the monarchy.

Giuseppinisti (Josephinism) was a policy initiated by Emperor Joseph II of Austria (reigned 1765–1790), aimed at subordinating the Catholic Church to the Austrian state and promoting enlightened absolutism. It extended beyond Austria into other Habsburg-controlled territories like Northern Italy.

[3] Kulturkampf is a German term meaning “culture struggle”, and it refers to a period of conflict in the 1870s between the German imperial government, led by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, and the Catholic Church, particularly in Prussia and other German states.

Desamortización refers to a series of state-led confiscations and sales of Church and communal property carried out primarily in Spain during the 19th century, under various liberal governments. The term comes from the Spanish verb desamortizar, meaning “to disentail” or “to release from mortmain” (i.e., from inalienable ownership, especially by the Church).

Guarentigie refers to the “Law of Guarantees” (Legge delle Guarentigie) enacted by the Italian Kingdom in 1871 after the capture of Rome. It was a unilateral law intended to define the relationship between the newly unified Italian state and the Papacy, following the end of the Papal States.

[4] The Synod of Pistoia was a diocesan synod convened in 1786 in the town of Pistoia, Tuscany, by Bishop Scipione de’ Ricci, under the protection of Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany (later Emperor Leopold II). It is one of the most important events in the history of Jansenist and proto-modernist reform movements within the Catholic Church in Italy.

[5] Unus inter pares is Latin for “one among equals,” referring to a view that denies the pope’s supreme authority over the bishops.

[6] Francesco Lamendola, Quanti preti di sinistra sono massoni ed ex agenti sovietici infiltrati nei seminari? il Corriere delle Regioni, Quaderni culturali: Giornale Web e www.ariannaeditrice.it [31.1.2017, pagina non più esistente] (Source: original essay by Gianandrea de Antonellis)

[7] Francesco Lamendola, I gesuiti hanno preso il timone della Chiesa, ma per condurla dove?, http://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articolo.php?id_articolo=53779 [7.02.2017]. (Source: original essay by Gianandrea de Antonellis)

[8] Thersites is a character from Homer’s Iliad. He serves as a literary embodiment of ugly, disorderly, and rebellious democratic sentiment, especially when contrasted with the heroic aristocratic ideals of the Greek epic tradition.