It’s strange what lingers in the mind. At a recent exhibition—The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy—I found myself thinking again of a line I once came across, or thought I did, long ago: “Mussolini is proof that a Prussian can be born south of the Alps,” or perhaps it was “Mussolini is the Prussian of the south.” Yet when I tried to trace it, I came up empty. Convinced it was in Emil Ludwig’s Talks with Mussolini (1933), I found nothing. Then, thinking it might appear in Ezra Pound’s Jefferson and/or Mussolini (1935), I searched again—with the same result. Even the web yielded no answer.

The Rape of Europa (c.1676) by Luca Giordano, State Hermitage Museum

Still, the idea had struck me so powerfully that I carried it for years, even applying it to myself. I was a European born on this side of the Atlantic. To me, “European” was never merely a biological or geographical designation but a spiritual and cultural one. I felt a deeper kinship with the old continent—its civilization rooted in Greece and Rome and later crowned by Christianity—than with Americanism and its descent into secularism, materialism, and Enlightenment rationalism. Yet, sadly, Europa today has become virtually indistinguishable from the American decadence I once longed to escape.

I have often wondered whether identity is something one inherits or something one remembers. Blood and soil may determine the coordinates of our birth, but the soul’s homeland is another matter. From childhood, I felt an unease that could not be explained by circumstance alone—a sense that I had awakened in the wrong time and place, like a traveler who opens his eyes on a foreign shore and recognizes nothing familiar except the stars.

In America today, to call oneself “European” is an act of nostalgia, if not defiance. It invites suspicion—an accusation of elitism, an affection for ghosts. Yet I could never quite renounce that lineage of mind and spirit: the music of Scarlatti, the marble of Sanmartino, the geometry of Castel del Monte, and the metaphysics of Aquinas and Vico. These were not museum pieces to me but living presences, the pulse of a civilization that once believed the world had meaning.

To be European in exile—in my case, Duosiciliano, Southern Italian—is to live in translation: to think in one language, metaphorically, while speaking in another; to feel one’s own values gradually lose their native ground. What others mistook for arrogance was, in truth, homesickness—a longing for a world where beauty, hierarchy, and faith still formed a coherent order.

Over time, that estrangement became less a wound than a vocation. To live between worlds is to see both more clearly. The American air, for all its vulgarity, sharpens one’s understanding of what Europe once was; the European inheritance, for all its decadence, preserves the memory of what the diaspora might yet become. I began to see that identity is not merely belonging, but fidelity—to a vision, to a standard, to something that transcends the accidents of birth.

In art, I sought the remnants of that older order: the measured harmony of the Middle Ages, the luminous stillness of Byzantium, the tragic dignity of Christendom. Even in fragments, they spoke a universal language—the grammar of form, proportion, and transcendence. It was as if Europe had left behind a trail of breadcrumbs for those still willing to find their way back.

What others called reaction, I came to understand as remembrance. To affirm beauty in an age of desecration, to uphold hierarchy in a time of leveling, to revere the sacred amid the machinery of progress—these were not refusals of the present but acts of fidelity to the eternal. Identity, I realized, is not where one stands on a map, but what one refuses to forget.

And so, that half-remembered phrase—whether it was ever written or only imagined—still feels true. “A Prussian born south of the Alps” was, perhaps, only a metaphor for every soul displaced between origins and ideals. I see now that what I once took for confusion was, in truth, a kind of destiny—to be born into one civilization yet called to serve the memory of another. We inherit ruins, yes—but also the duty to remember what they once meant. If I, too, am a European born elsewhere, so be it; for identity, in the end, is not a matter of geography, but of fidelity—to the civilization one refuses to betray.

~ By Giovanni di Napoli, October 16th, Feast of San Gerardo Maiella

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

O God, who has placed a great light in Your saints and a provident support for Your people along the path, listen with goodness to our prayer, and glorify Your servant Maria Cristina di Savoia, in whose life as a wife and queen You have offered us a shining model of wise and courageous charity, and grant us, through her intercession, the grace [mention here the graces you are asking for] which from You, with trust, we invoke. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

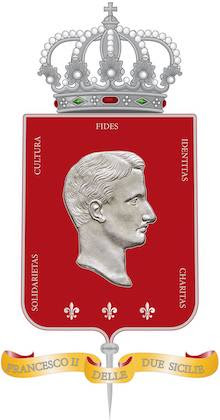

O One and Triune God, Who casts Your glance on us from Your throne of mercy, and called Francis II of Bourbon to follow You, choosing him on earth to be king, modeling his life on the very Kingship of Jesus Christ, crucified and risen, pouring into his heart sentiments of love and patience, humility and meekness, peace and pardon, and clothing him with the virtues of faith, hope and charity, hear our petition, and help us to walk in his footsteps and to live his virtues. Glorify him, we pray You, on earth as we believe him to be already glorified in Heaven, and grant that, through his prayers, we may receive the graces we need. Amen

Introduction

Il Regno is not a formal membership organization. We are a circle of like-minded individuals based in Brooklyn, New York, who volunteer our time and efforts to preserve and promote our Duosiciliano (Southern Italian) heritage, culture and faith. The title of our journal is an allusion to the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was often simply referred to as il Regno, or the Kingdom. We are Catholic, Monarchist and support the Neobourbon cause. Viva Cristo Re!

Contact: ilregno2s@yahoo.com

Search Il Regno

Archives

-

▼

2025

(891)

- October (48)

- September (57)

- August (71)

- July (94)

- June (102)

- May (106)

- April (101)

- March (96)

- February (100)

- January (116)

-

►

2024

(470)

- December (73)

- November (71)

- October (29)

- September (18)

- August (21)

- July (29)

- June (34)

- May (31)

- April (42)

- March (47)

- February (34)

- January (41)

-

►

2023

(397)

- December (32)

- November (23)

- October (50)

- September (52)

- August (49)

- July (26)

- June (26)

- May (26)

- April (30)

- March (26)

- February (28)

- January (29)

-

►

2022

(245)

- December (23)

- November (21)

- October (21)

- September (22)

- August (28)

- July (17)

- June (19)

- May (18)

- April (25)

- March (14)

- February (16)

- January (21)

-

►

2021

(192)

- December (17)

- November (25)

- October (7)

- September (14)

- August (24)

- July (19)

- June (12)

- May (19)

- April (15)

- March (13)

- February (13)

- January (14)

-

►

2020

(279)

- December (21)

- November (19)

- October (33)

- September (22)

- August (37)

- July (22)

- June (24)

- May (18)

- April (22)

- March (19)

- February (21)

- January (21)

-

►

2019

(215)

- December (25)

- November (27)

- October (27)

- September (31)

- August (14)

- July (8)

- June (12)

- May (12)

- April (19)

- March (12)

- February (11)

- January (17)

-

►

2018

(260)

- December (18)

- November (16)

- October (25)

- September (33)

- August (31)

- July (22)

- June (19)

- May (15)

- April (24)

- March (27)

- February (16)

- January (14)

-

►

2017

(238)

- December (17)

- November (19)

- October (26)

- September (18)

- August (28)

- July (21)

- June (23)

- May (21)

- April (25)

- March (14)

- February (12)

- January (14)

-

►

2016

(245)

- December (24)

- November (20)

- October (27)

- September (20)

- August (23)

- July (25)

- June (24)

- May (21)

- April (15)

- March (20)

- February (13)

- January (13)

-

►

2015

(219)

- December (21)

- November (19)

- October (25)

- September (23)

- August (26)

- July (21)

- June (20)

- May (16)

- April (13)

- March (13)

- February (9)

- January (13)

-

►

2014

(121)

- December (11)

- November (9)

- October (13)

- September (18)

- August (17)

- July (9)

- June (13)

- May (8)

- April (5)

- March (7)

- February (7)

- January (4)

-

►

2013

(109)

- December (4)

- November (6)

- October (8)

- September (15)

- August (15)

- July (12)

- June (9)

- May (11)

- April (11)

- March (5)

- February (6)

- January (7)

-

►

2012

(87)

- December (12)

- November (5)

- October (8)

- September (13)

- August (10)

- July (8)

- June (6)

- May (5)

- April (6)

- March (5)

- February (4)

- January (5)

-

►

2011

(78)

- December (6)

- November (4)

- October (6)

- September (7)

- August (6)

- July (7)

- June (4)

- May (6)

- April (5)

- March (11)

- February (8)

- January (8)

Labels

Prayer for Blessed Maria Cristina, Queen of the Two Sicilies

O God, who has placed a great light in Your saints and a provident support for Your people along the path, listen with goodness to our prayer, and glorify Your servant Maria Cristina di Savoia, in whose life as a wife and queen You have offered us a shining model of wise and courageous charity, and grant us, through her intercession, the grace [mention here the graces you are asking for] which from You, with trust, we invoke. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

Prayer for SG Francesco II, King of the Two Sicilies

O One and Triune God, Who casts Your glance on us from Your throne of mercy, and called Francis II of Bourbon to follow You, choosing him on earth to be king, modeling his life on the very Kingship of Jesus Christ, crucified and risen, pouring into his heart sentiments of love and patience, humility and meekness, peace and pardon, and clothing him with the virtues of faith, hope and charity, hear our petition, and help us to walk in his footsteps and to live his virtues. Glorify him, we pray You, on earth as we believe him to be already glorified in Heaven, and grant that, through his prayers, we may receive the graces we need. Amen

Epigraphs

We have no aspirations other than to continue to make those sacrifices, to the day we give our lives, if necessary, to defend the cause of our King. The sword that we brandished in Spain, we shall draw again to fight in favor of legitimacy wherever it becomes necessary: the revolutionaries are the same everywhere, and their plans are always iniquitous. The usurpation that has been committed to the detriment of the King of Naples cries out for deserved vengeance, and we consider it a great honor to lend a hand. ~ Francesc Tristany

Better a good death than a bad life. ~ Neapolitan proverb

The secret of the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment of life is: to live dangerously! Build your cities under Vesuvius! ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

The blackest despair that can take hold of any society is the fear that living rightly is futile. ~ Corrado Alvaro

It's an ill bird that fouls its own nest. ~ English proverb

What is needed is not a revolution in the opposite direction, but the opposite of a revolution. ~ Joseph de Maistre

The tricolor! Tricolor indeed! They fill their mouths with these words, the rascals. What does that ugly geometric sign, that aping of the French mean, compared to our white banner with its golden lily in the middle? What hope can those clashing colors bring them? ~ Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

Blogroll

Fondazione Francesco II delle Due Sicilie

Help Support The Roman Forum

Papal Zouave International

La Famiglia Degli Apostolati

Recommendations (Italian)

Recommendations (English)

Visitors

© 2009-2025 Il Regno. All rights reserved